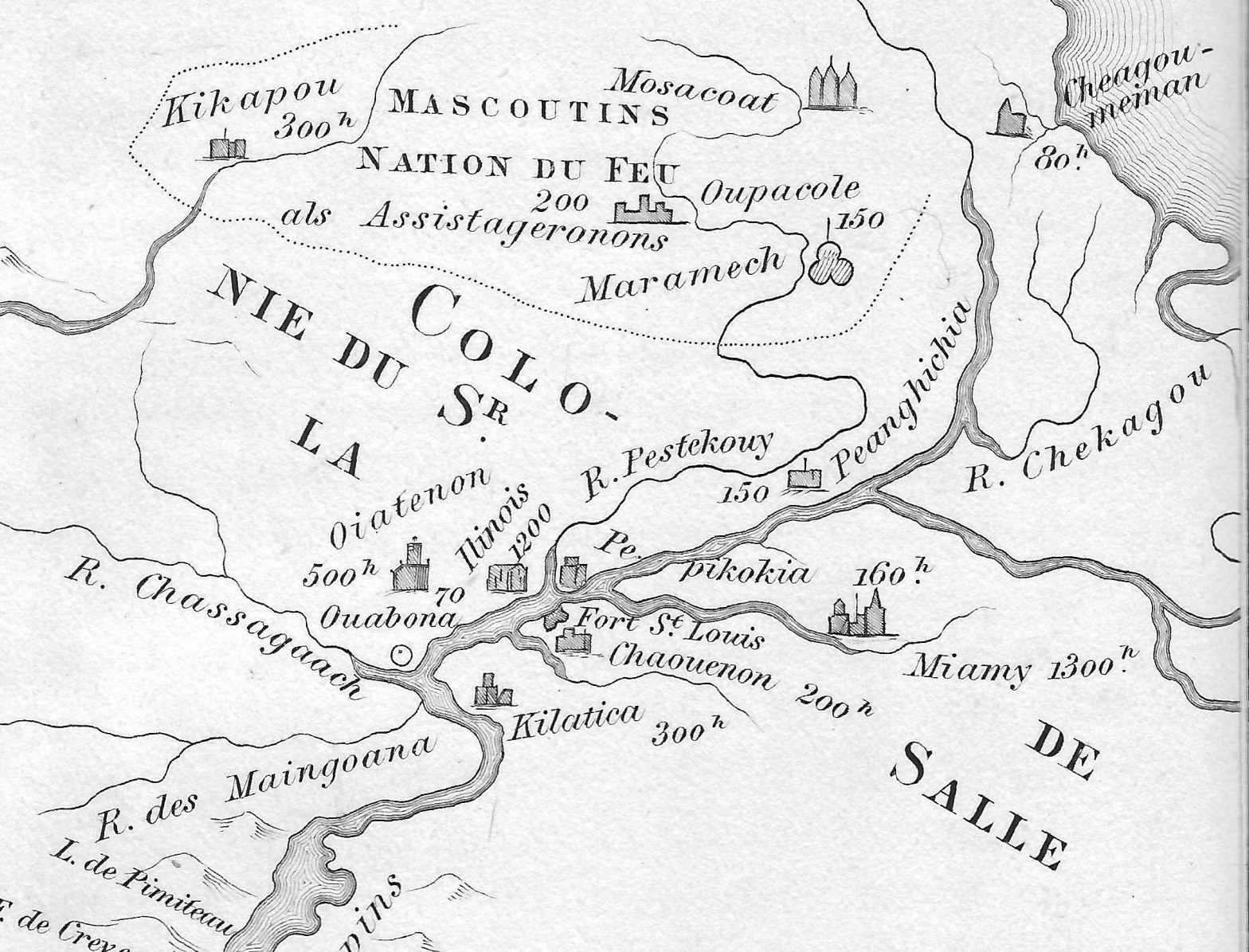

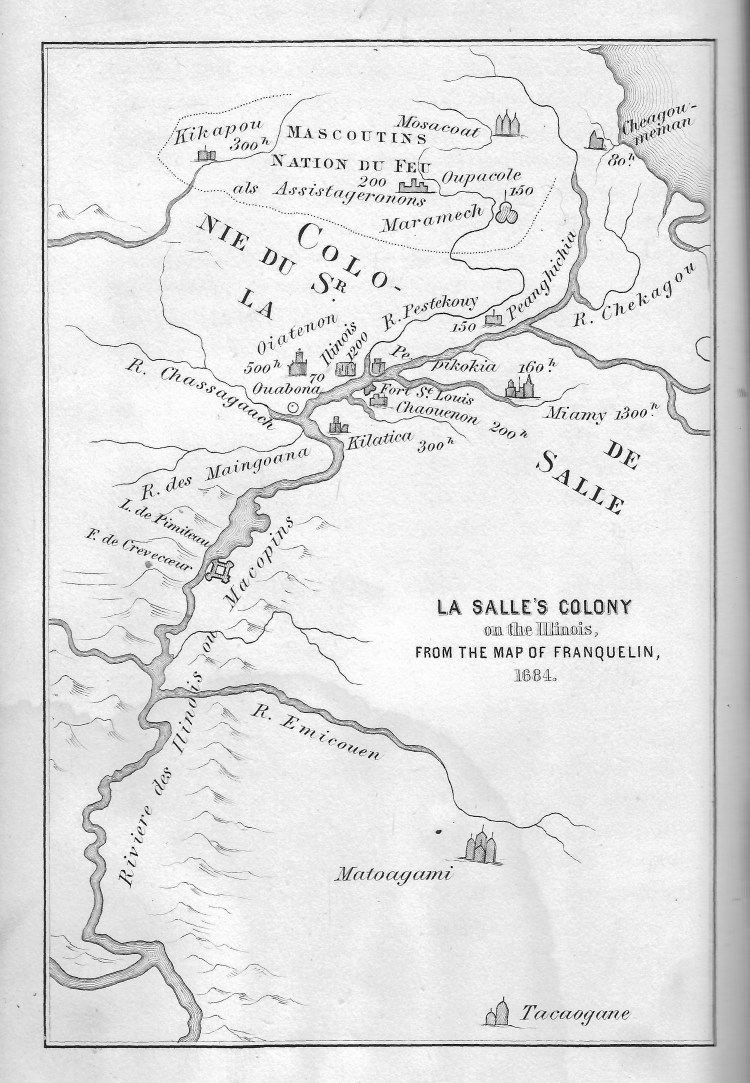

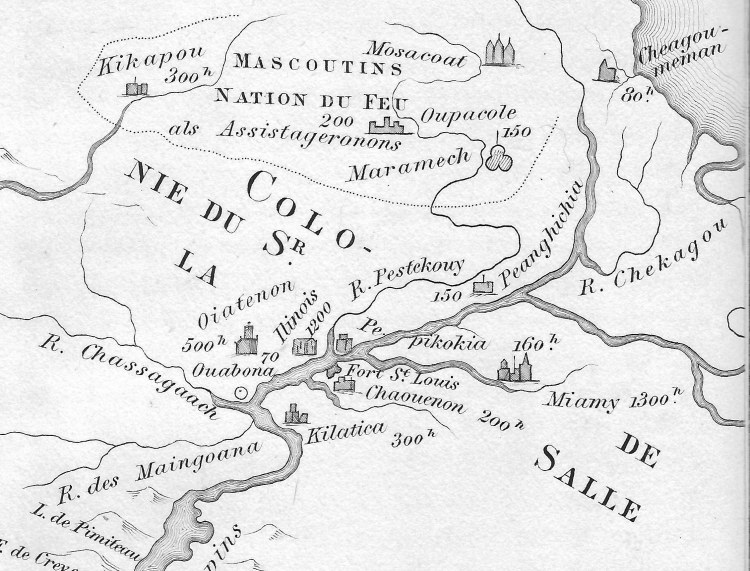

Amidst political intrigue on all fronts, Renè-Robert Cavalier, Sieur de La Salle and his able Lieutenant Henri de Tonty, spent the first months of the year 1683 building a fort deep in the woods of North America. They constructed Fort St. Louis upon a huge outcropping of rock overlooking the Illinois River, known today as Starved Rock near Ottawa, Illinois. They also encouraged Native Americans to join them, and in so doing, they established an incipient colony. The “COLONIE DU Sr. DE LA SALLE” is shown on this 1684 map by Franquelin, as discussed in a previous article. The map captures a snapshot of the great gathering of Native Americans and a few Frenchmen, in the summer of 1683.

Who made up this colony? Who were they and why were they there?

In his book, La Salle and the Discovery of the Great West, Francis Parkman reproduced Franquelin’s representation of the colony.

Zooming in on the “colony” we see groups of Native Americans identified by tribe, with numbers of warriors.

The numbers on the map correspond with La Salle’s report to the Minister of the Marine in France, stating that there were nearly four thousand warriors encamped around his fort. Adding women, children, and men not considered warriors, the total number of natives was approximated at twenty thousand.

The warriors by tribe, shown on Franquelin’s map, presumably as reported to him directly by M. de La Salle:

Illinois, 1200

Miami, 1300

Shawanoes, 200

Ouiatenons (Wea), 500

Peanqhichia (Piankishaw), 150

Pepikokia, 160

Kilatica, 300

Ourabona, 70

This gathering of warriors and their tribes was not normal. Indeed, it was exceptional. Driven by fear of their common enemy, the Iroquois Confederacy, these Algonquin speaking Indians had abandoned their traditional geographic regions and had drawn together for protection. Force in numbers. Belief in the French as protectors. Confidence in La Salle as the man who would keep them from being slaughtered by the Iroquois.

The politics were intense. La Salle was attempting to establish the basis of a French empire in the heart of North America. The English and Dutch were encouraging the Iroquois to create havoc among the traditional native inhabitants of the region in an effort to prevent the French from gaining a foothold and from monopolizing the fur trade with the natives. The new French Governor of Canada, perceiving La Salle as a competitor, was also encouraging the Iroquois to create trouble while undermining La Salle. Though La Salle had permission from the King to engage in these activities, the Governor was withholding support in the form of soldiers, supplies, and weapons. Amidst the political intrigue, there stood La Salle, looking out over the Illinois valley, looking over a sea of humanity the likes of which this region had never known.

Quoting Parkman, “La Salle looked down from his rock on a concourse of wild human life. Lodges of bark and rushes, or cabins of logs, were clustered on the open plain or along the edges of the bordering forests. Squaws labored, warriors lounged in the sun, naked children whooped and gambolled on the grass. Beyond the river, a mile and a half on the left, the banks were studded once more with the lodges of the Illinois, who, to the number of six thousand, had returned, since their defeat [to the Iroquois], to this their favorite dwelling-place. Scattered along the valley, among the adjacent hills, or over the neighboring prairie, were the cantonments of a half-score of other tribes, and fragments of tribes, gathered under the protecting aegis of the French.” (Parkman, p.295).

Meanwhile, La Salle had a grander plan in mind. Having recently successfully navigated the Mississippi River to its mouth at the Gulf of Mexico, he had claimed all the lands drained by the Mississippi for France. La Louisiane, he called it, in honor of his King, Louis XIV. He planned to establish another French stronghold near the mouth of the great river so that he could fend off the Spanish from the south and control trade throughout the entire region. In order to do this, he needed to travel to France to plead his case to the King and make clear his voice amidst the political intrigue. Hence, having built his fort and established his colony, he departed. La Salle left his colony in the able hands of Tonty, canoed to Quebec, and sailed for France. It was up to Tonty to hold the fort, maintain the coalition of natives in the face of further political intrigue from his own allies, and fend off the Iroquois.

Fend them off, he did. In Tonty’s own words, in a report written from Quebec in November, 1684, Tonty stated, “On the 21st of March, 1684, two hundred Iroquois, after robbing seven French canoes, came to attack our Fort. After six days’ siege, they retired with loss and were pursued by small parties of our allies, who killed some of them.” (Tonty, p.115)

The Colony did not last. La Salle never returned and the natives eventually dispersed. But the great gathering of warriors and their families did occur in the years 1683-1684 in the heart of the woods of North America, memorialized in maps and journals.

Sources:

Francis Parkman, La Salle and the Discovery of the Great West, Twelfth Edition. Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1884

Relation of Henri de Tonty Concerning the Explorations of LaSalle from 1678 to 1683, translated from French by Melville B. Anderson, The Caxton Club, Chicago, 1898

Excerpt from Franquelin’s 1884 map compliments of the U.S. Library of Congress

Images of Parkman’s reproduction of the Colony of La Salle scanned from personal copy of La Salle and the Discovery of the Great West. See above reference.