This is a reprint of an article originally published in the Fall 2015 edition of the Hoosier Surveyor, the quarterly magazine of the Indiana Society of Professional Land Surveyors. The magazine may be viewed by clicking this link: Hoosier Surveyor Volume 42-2. The full article is printed below.

Who Sold the New Purchase?

By Jim Swift

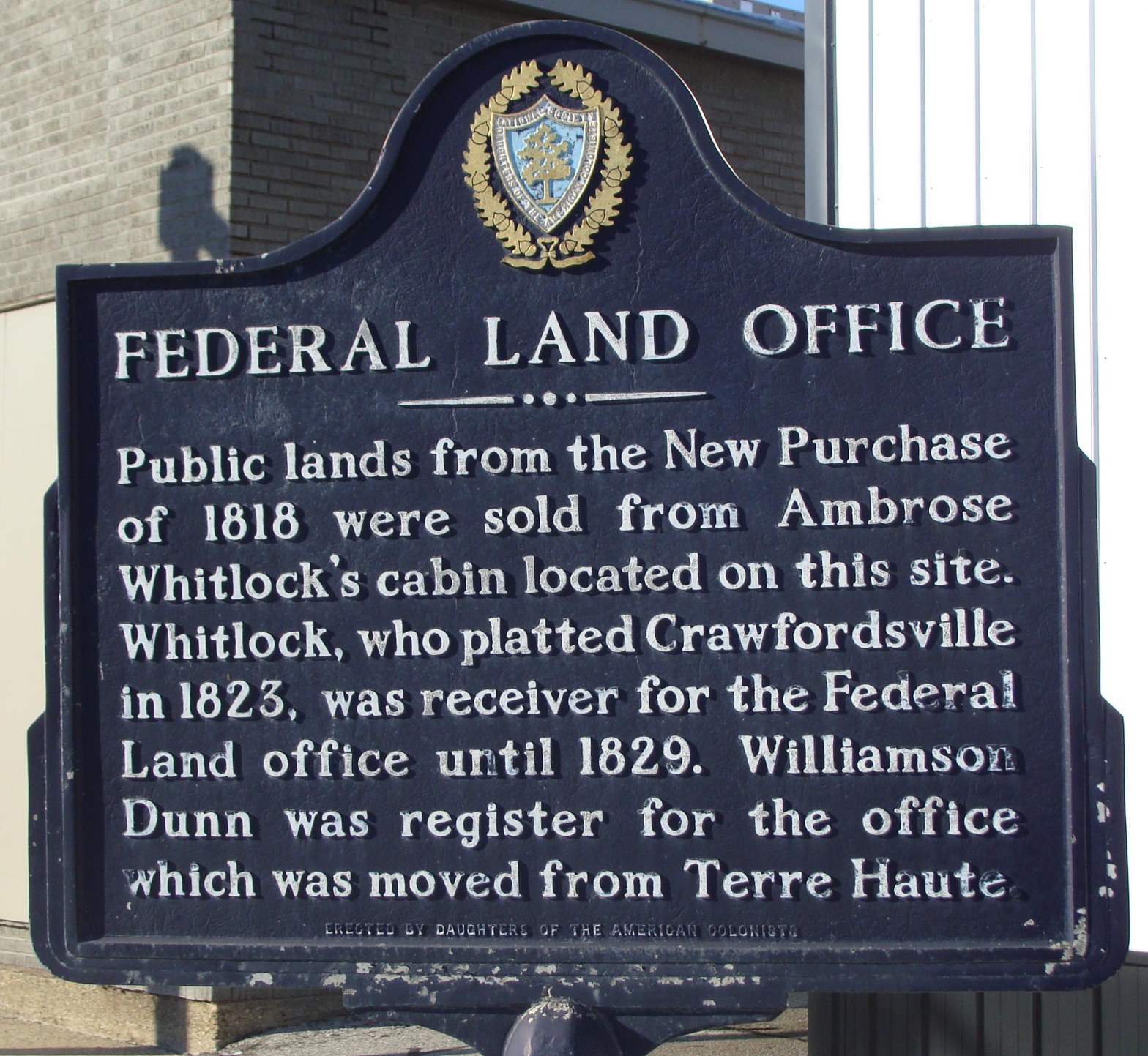

Some years ago, I was riding a bicycle through my home town of Crawfordsville, Indiana, when I stopped to read this historical marker.

The idea of a Land Office sounded pretty cool to me and, being a local kid, I was familiar with the names Whitlock and Dunn. But what, I wondered, was the New Purchase? Clearly it was a land purchase, but purchased from whom? I mentally reviewed my basic U.S. History. I knew that this area was once claimed by France. I also knew that Great Britain had ceded it to the U.S. Government at the conclusion of the Revolutionary War. Being an astute young bicyclist, I concluded that since we had gained rights to the land from Britain by the conquest of war, I figured we probably did not need to purchase it from them as well. Surely, we didn’t have to pay for the ground we had won through victory at war. I peddled my bicycle away that afternoon puzzling on the question of who sold the land bought in the New Purchase?

That evening I did a little research and discovered that the United States Government had purchased the land from the native inhabitants, the Indians. That was an interesting concept to me. I had never before thought about the idea that the U.S. Government might have actually purchased this land from the Indians. How, I wondered, did all of that work? Which Indians? What specific land? How much did we pay? I puzzled on those questions as I went to bed that night. 30 years later, they are still interesting.

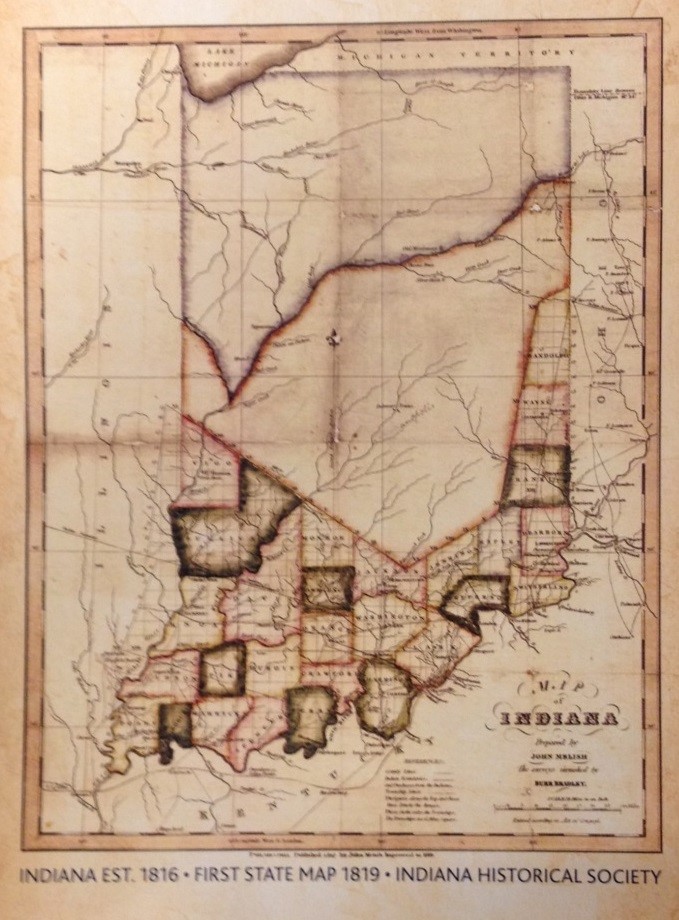

In 1816, Indiana was admitted the Union as the 19th member of the United States of America. Below is the first map of the State of Indiana, dated 1819. This particular image is a photograph of a post card recently mailed by the Indiana Historical Society.

Note the areas which appear to be divided into counties, comprising the approximate southern one-third of the state. At the time of admission to the Union, these areas had already been purchased from the Indians, in one case after a hard won victory at battle, and were comfortably under treaty. The land to the north, being the northern two-thirds of the state, was not yet secured by treaty. Based in English law, our concepts of land ownership clearly dictated that before we could survey, sell or settle an area, we needed to secure treaties to the land from the native inhabitants. By 1818, Jonathon Jennings, the first Governor of Indiana, was quite anxious to open the central part of the new state to settlement and he pushed hard for treaties with the Indians. Much negotiation took place. Jennings and the federal agents were on one side and the various native tribes were on the other. Ultimately the negotiations yielded agreements and in early October, 1818, at St. Mary’s, Ohio, four separate treaties were concluded. Each treaty represented a separate negotiation between the United States of America and the respective tribes, the Potawatamie, Wea, Delaware and Miami. Each treaty is different, negotiated under different terms. The combined set of treaties is commonly referred to as the New Purchase. Notably, the Shawnee Tribe, which had made a splash in the Indiana Territory just a few years earlier through the exploits of Tecumseh and his brother The Prophet, is not mentioned in any of the treaties.

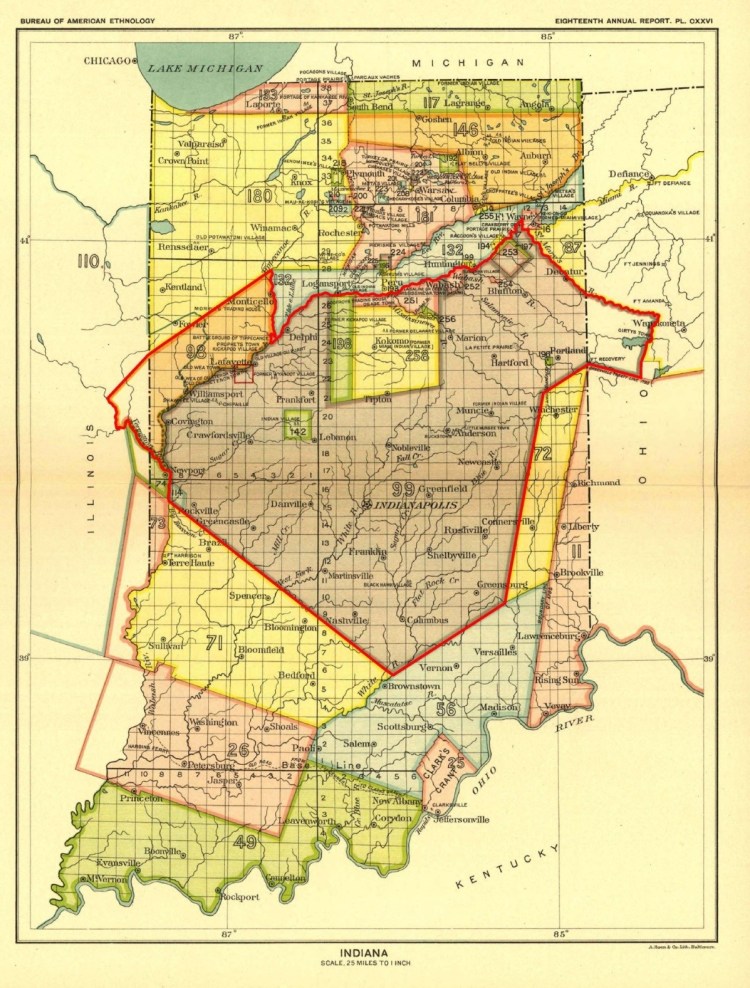

The following image, being a map by Charles C. Royce (see previous article in the Hoosier Surveyor, Summer 2015), shows the various treaty parcels in Indiana. I have outlined the perimeter of the areas addressed by the New Purchase in red.

The Potawatamie Tribe was the first to sign a treaty, concluded on October 2, 1818. The orange colored parcel, number 98, in the northwest portion of the New Purchase represents that area which was granted to the U.S. by them. The treaty describes the ceded territory as, “Beginning at the mouth of the Tippecanoe river, and running up the same to a point twenty-five miles in a direct line from the Wabash river—thence, on a line as nearly parallel to the general course of the Wabash river as practicable, to a point on the Vermilion river, twenty-five miles from the Wabash river; thence, down the Vermilion river to its mouth, and thence, up the Wabash river, to the place of beginning.“ The treaty also states, “The Potawatamies also cede to the United States all their claim to the country south of the Wabash river.” In return, “The United States agree to pay to the Potawatamies a perpetual annuity of two thousand five hundred dollars in silver; one half of which shall be paid at Detroit, and the other half at Chicago; and all annuities which, by any former treaty, the United States have engaged to pay to the Potawatamies, shall be hereafter paid in silver.”

Annexed to the treaty is a schedule of grants to private individuals, most of whom are named Burnett. I believe the Burnetts were the children of a Potawatamie woman who was the sister of a chief, and a French trader named Burnett who had established a trading post along the Wabash River near the mouth of the Tippecanoe River. Surveyors working in Tippecanoe County may be familiar with the Burnett Reserve in the area of Prophetstown State Park.

The next natives to sign a treaty were the Wea, also on October 2, 1818. Per the treaty, “The said Wea tribe of Indians agree to cede to the United State all the lands claimed and owned by the said tribe, within the limits of the states of Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois.” But they reserved a small area for themselves, being an approximately seven mile by seven mile rhombus shaped area at the mouth of Raccoon Creek, west of present day Rockville. This reserve is shown as the blue colored parcel number 114 in the southwest part of the New Purchase. For this, the Wea received the promise that, “…the United States agree to pay to the said Wea tribe of Indians, one thousand eight hundred and fifty dollars annually, in addition to the sum of one thousand one hundred and fifty dollars, (the amount of their former annuity,) making a sum total of three thousand dollars; to be paid in silver, by the United States, annually, to the said tribe, on the reservation described by the second article of this treaty.”

Note the interesting condition that the Potawatamies had to travel to Detroit and Chicago to receive their annual annuity of silver, but the Weas were to receive theirs at the reservation.

The Wea treaty also promised to grant one section of land each to two different women, both of whom were daughters of the sister of a chief.

The next day, on October 3, 1818, representatives of the Delaware Tribe signed a treaty. The Delaware were not historically from this area. They were once known as the Lenape and had migrated from the East Coast, roughly the Delaware/New Jersey area, and had been hunting the lands of the White River in central Indiana. In 1809 they had secured an acknowledgement from the Miami of equal right “to the country watered by the White River.” But they must not have felt at home here, because they basically gave up and agreed to leave the area entirely. Per Article One of the Treaty with the Delaware, “The Delaware nation of Indians cede to the United States all their claim to land in the state of Indiana.” They were promised land west of the Mississippi River, along with “one hundred and twenty horses, not to exceed in value forty dollars each, and a sufficient number of perogues, to aid in transporting them to the west side of the Mississippi; and a quantity of provisions, proportioned to their numbers, and the extent of their journey.” They were guaranteed an annuity of four thousand dollars in silver and given three years to vacate the area.

Later the same day, October 3, 1818, the last of the four treaties was concluded with the Miami tribe. They were represented in negotiation by a man known to the Miami as Peshawa and known to Jonathon Jennings and the federal agents as Jean Baptiste de Richardville. He was the son of a French fur trader and a Miami woman who was the sister of a prominent Miami Chief. By all accounts, Richardville was a shrewd businessman. He was fluent in the English, French and Miami languages and he was a fabulous negotiator. It seems he comprehended the importance Jennings placed on opening the central part of his young state to development. He must have known the value of the land, for he negotiated what appears to have been an excellent deal for both his followers and himself, if, that is, one accepts that any of the deals the natives made with the American Government were ultimately good deals. In any case, it appears to have been a much better deal than those made by the other tribes participating in the New Purchase. Refer to the above map and imagine that Jennings’ primary goal was to secure title to all of the land south and east of the Wabash River. Note the numerous green, yellow and brighter pink reserves, including parcels 142, 188, 251-253, and 258. Those areas were all reserved out of the New Purchase by the Miami, along with many private grants, the promise of a saw mill, grist mill, agricultural equipment and a perpetual annuity of fifteen thousand dollars.

The Treaty with the Miami is long, detailed, and makes reference to several interesting concepts. Together with the fascinating character, Jean Baptiste de Richardville, it is worthy of an article itself. For now, I will leave it at that, offering the reader the opportunity to puzzle on another interesting question. How is it that, while the general fortunes of the Indians were fading, the Miami Chief Peshawa became known as the richest man in Indiana?

Author’s note on spelling: in the above article the tribe commonly known as the Potawatomi is spelled as Potawatamie per the treaty being quoted. This name appears in U.S. Treaties under several various spellings. Whatever the variations on the spellings, the tribe is believed to be the same.