As the 17th century yielded to the 18th, France was a remarkable, powerful nation. King Louis XIV, the Sun King, had been on the throne for more than 50 years. Administrative power in France was centralized around the royal court, the once powerful Spain was coming under the influence of France, and the province of New France in North America was steadily growing.

Among the myriad of enterprises under the sphere of the French royal household, mapping North America was one which might have fallen under the general heading of Public Relations. Today we may think of maps as presentations of geographical knowledge, committed to accuracy and correct information. On some counts the French court of the 18th century had the same idea and employed the Cassini family to produce accurate, precise maps of France. But the making of maps, particularly of North America, also had another, grander purpose. To make a map was to claim the ground. Detailed maps of North America were an expression of ownership by France over the interior of the continent, the vast territories of Canada and Louisiana. Accuracy was not necessarily as important as the simple fact that the map existed. Hence, early French maps are interesting to study today, both for what kind of information is presented and for how accurate that information was. Given that numerous such maps were made, there exists ample opportunity to compare and contrast. Who knew what when? And what information was included on a map which might not have been known at all?

This article looks at two maps, with a focus on several rivers of the current American Midwest.

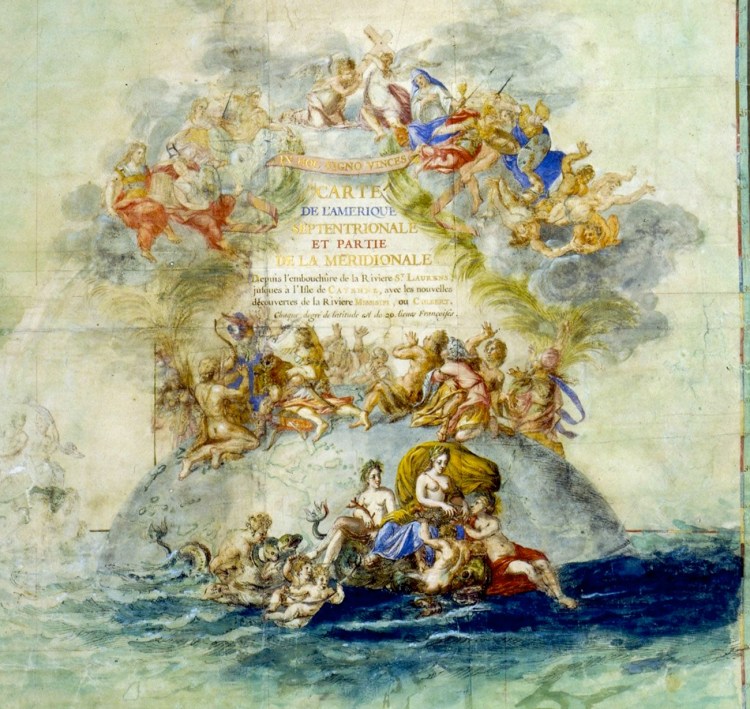

Some French maps were beautiful, drawn with an artistic flair, like this map by Claude Bernou from 1681.

One must appreciate the elegant style of the title.

The detail of the Great Lakes is impressive, though knowledge of the lands to the south and west of the lakes appears to be limited.

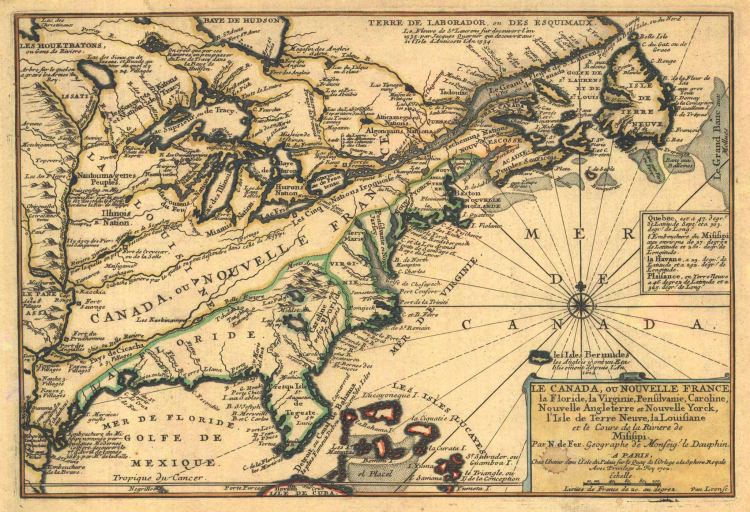

Other maps are presented in a more practical, less artistic fashion. Here is a French map published in 1702.

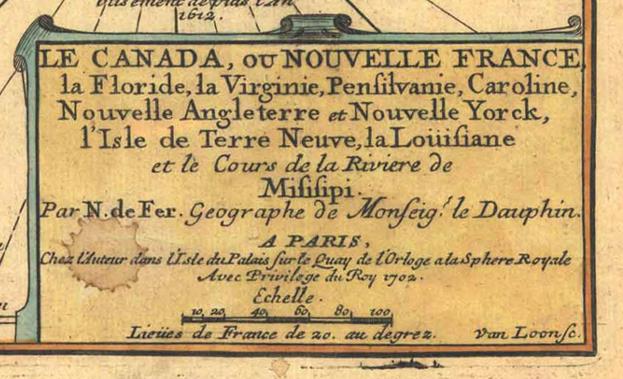

Check out the plain, informative title block:

Written in French, the may be approximately translated as, “Canada, or New France, Florida, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Carolina, New England, New York, Newfoundland, Louisiana and the Course of the Mississippi River. By N. de Fer, Geographer of Monseigneur le Dauphin, at Paris, at the establishment of the author in the Island of the Palace, on the “Quay de L’Orloge” [de Fer’s shop] in the Royal Sphere, with privilege of the King, 1702.”

De Fer refers to Nicolas de Fer, Geographer and Cartographer for Louis, Le Grand Dauphin of France, also known as Monseignuer le Dauphin (1661-1711). Please note that Dauphin is the French term for Crown Prince. Indeed, Louis, Le Grand Dauphin, was the son of the King Louis XIV and heir to the throne. Nicolas de Fer operated a successful business in Paris specializing in cartography, printing and engraving. He made a vast number of maps related to the business of the French kingdom, eventually becoming the official Geographer for Louis XIV and Louis’ grandson, King Phillip V of Spain. Notably, de Fer’s life span of 1646-1720 closely coincides with the reign of King Louis XIV, 1643-1715.

Here is a portrait of Nicolas de Fer, compliments of Wikipedia Commons.

And here is a portrait of his client, Louis, Le Grand Dauphin, also compliments of Wikipedia Commons. The Dauphin did not outlive his father and never became King, though his second son became King Phillip V of Spain, and his grandson became King Louis XV of France.

Along with other purposes, including the aforementioned claim of ownership, it appears to me that one goal of this map is to demonstrate transportation routes in the form of rivers and lakes. It is well known that French trappers and traders could potentially travel from the St. Lawrence Seaway to the Gulf of Mexico, almost entirely on water. The tricky part was to get from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River. This was accomplished via several critical portages, the locations of which are demonstrated on this map. Let’s zoom in on the Great Lakes and the surrounding territory.

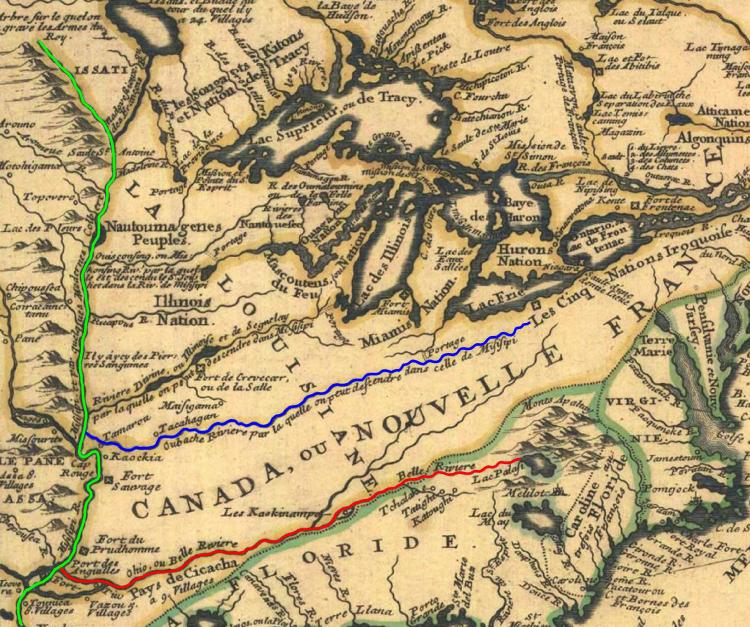

Here is the same view with three rivers highlighted. The Mississippi is green, the Ohio red, and the Wabash River blue.

Note the writing along the Wabash River. “Oubache Riviere par la quelle on peut descendre dans celle de Misisipi,” which roughly translates to “Wabash River by which one is able to descend to the Mississippi.” YIKES! It is true that one can descend to the Mississippi via the Wabash, but there is a huge problem here. The Wabash River empties into the Ohio River, not the Mississippi. Waters of the Wabash only get to the Mississippi after they have mingled with the Ohio. I do not know from whom Monsieur Nicolas de Fer got his information, but this presentation of the Wabash River is blatantly wrong. At least one previous French map (Franquelin, 1684) did get the course of the Wabash approximately correct, but clearly M. de Fer did not adhere to this interpretation. Who provided the information that the Wabash River was a route to the Mississippi? Did they not notice that the river merged with another, larger river before it reached the Mississippi? If so, this information had evidently not been passed onto the cartographer.

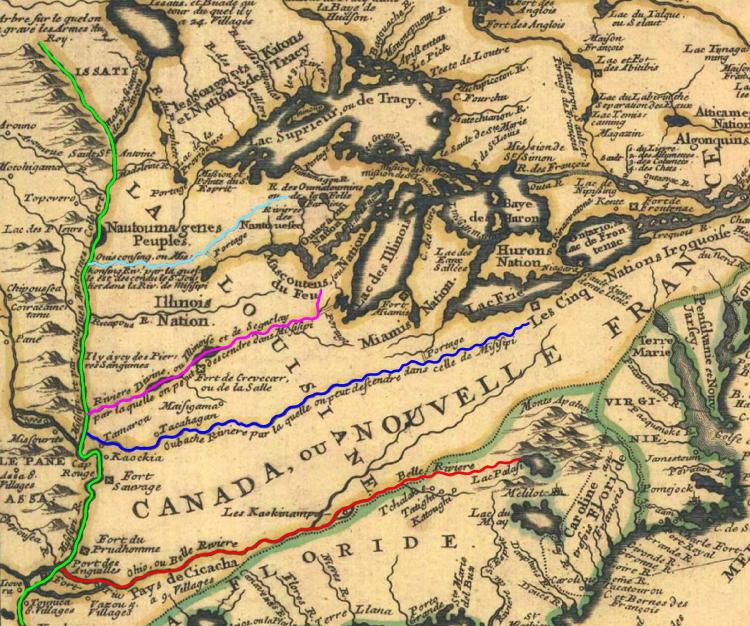

Here is the same view again with two additional rivers highlighted. The Illinois River is purple and the Wisconsin River is light blue.

The writing next to the Illinois is similar to that of the Wabash, indicating it to be a route to the Mississippi, though clearly there is some debate as to whether this river is called the Illinois or the Riviere Divine.

The writing along the Wisconsin River is more detailed, and perhaps more credible. “Ouisconsing ou Miskonsurg, par la quelle est descendu le S. Jolliet dans la Riv. de Misisipi.” This roughly translates to Wisconsin, or Miskonsurg River (?), by which Jolliet descended to the Riv. Mississippi.” Not only can one descend the Wisconsin to the Mississippi, but de Fer knew that someone had.

Indeed, in 1673, Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliette set out to find a way from what we now know as the Green Bay (Lake Michigan) to the Mississippi River. With information from the natives, Jolliette and his men paddled up the Fox River to a marshy lowlands near its headwaters. From there they carried their canoes approximately two miles to the Wisconsin River, which empties into the Mississippi at present day Prairie du Chien (French for Prairie of the Dog). The spot on the Wisconsin River where the portage is most convenient became known by the French fur traders as “Le Portage” and is yet known today as city of Portage, Wisconsin.

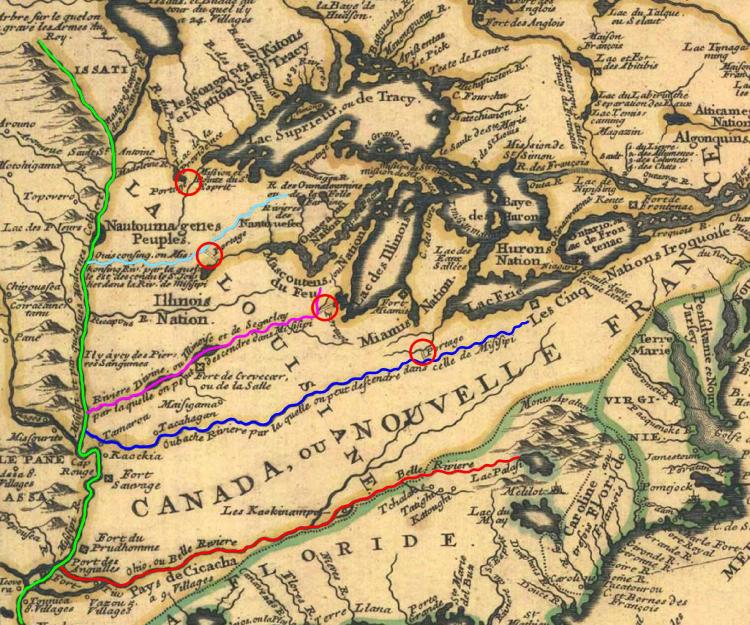

The final view I would like to share of this map is that of the five rivers and the various portages, as shown below.

The portage on the Wabash River is at modern day Fort Wayne, Indiana, where the Maumee River comes close to the Wabash. The ancient portage on the Illinois River is the modern city of Chicago. Notably, this portage may have been first discovered by Europeans on the same expedition by Jolliette in 1673. The portage on the Wisconsin River is, as noted above, at Portage, Wisconsin. The northern most portage shown on the diagram appears to be in the general vicinity of Duluth, Minnesota. I confess my confusion and lack of information about this particular feature of the map, as the well-known portage from Lake Superior began at present day Grand Portage, Minnesota, much further up the northern coast of Lake Superior.

Looking at the rivers and portages highlighted, the strategic importance of these critical links from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River is evident. They were critical to French trade between the the sub-provinces of Canada and Louisiana. They were critical to Britain after it won this area from France at the close of the Seven Years war in 1763, and they were critical to the United States of America prior to the construction of the railroads.

Another notable feature of this area of the map is the inclusion of names of the native tribes and the locations of villages and forts. However, other French maps from this era are much more detailed and interesting with respect to this information, providing more interesting opportunities for comparison and contrast. These topics are better addressed with respect to other maps.

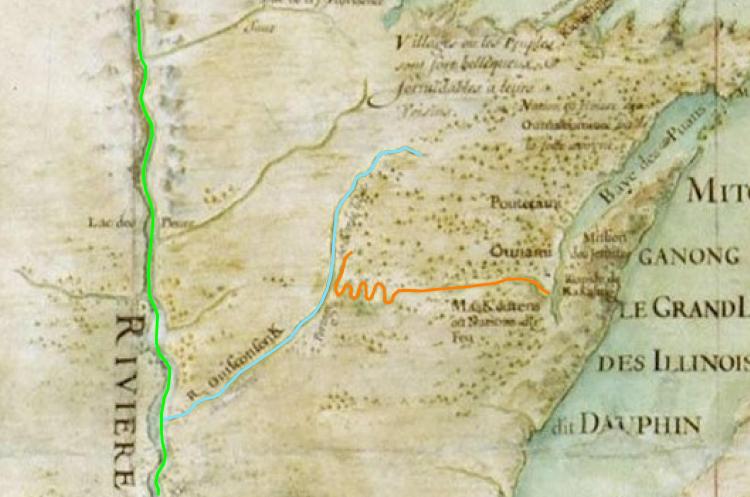

Before closing, let’s look back at the Bernou map of 1681. Though portages do not appear to be a top priority of this map, it is evident that Bernou had heard of the travels of Joliette in 1673. Note the detail with which the Wisconsin and Fox Rivers are presented. For convenience, the Wisconsin River is highlighted in light blue, the Fox in orange, and the Mississippi in green. Though vague on this copy of the map, it appears the word “portage” is noted at the appropriate spot.

That question as to whether the Illinois River was really Divine? Apparently Bernou accepts the latter title. And he clearly knew about the portage at Chicago.

But Bernou appears to have known little about the Wabash. He had information that a major river existed between the Divine and the Ohio but the route is not certain. Called the Aramoni, the river is shown vaguely to empty into the Divine.

Alas, they made impressive maps, but neither Bernou nor de Fer showed the Wabash River draining to the Ohio.

Note on sources: All base images shown hereon are believed to be in the public domain. Colored highlighting is the work of the author of this article. Nothing presented here is considered to be under copyright, including the author’s own work.