This is a reprint of an article originally published in the Summer 2015 edition of the Hoosier Surveyor, the quarterly magazine of the Indiana Society of Professional Land Surveyors. The magazine may be viewed by clicking this link: Hoosier Surveyor, volume 42-1. The full article is printed below.

A Marvelous Map

by Jim Swift

One thing most surveyors seem to have in common is a genuine interest in maps. Maps of all forms. Particularly maps of the geographic area in which they survey. We can’t help it. We’re map kind of people. Given the map friendly audience at the Hoosier Surveyor, I would like to introduce you to my favorite map.

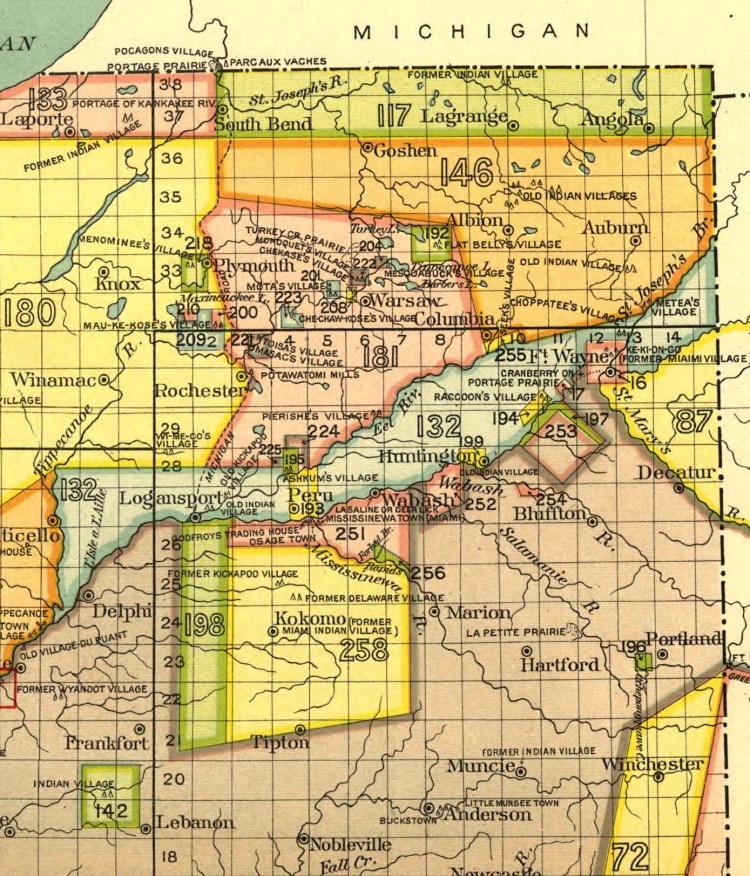

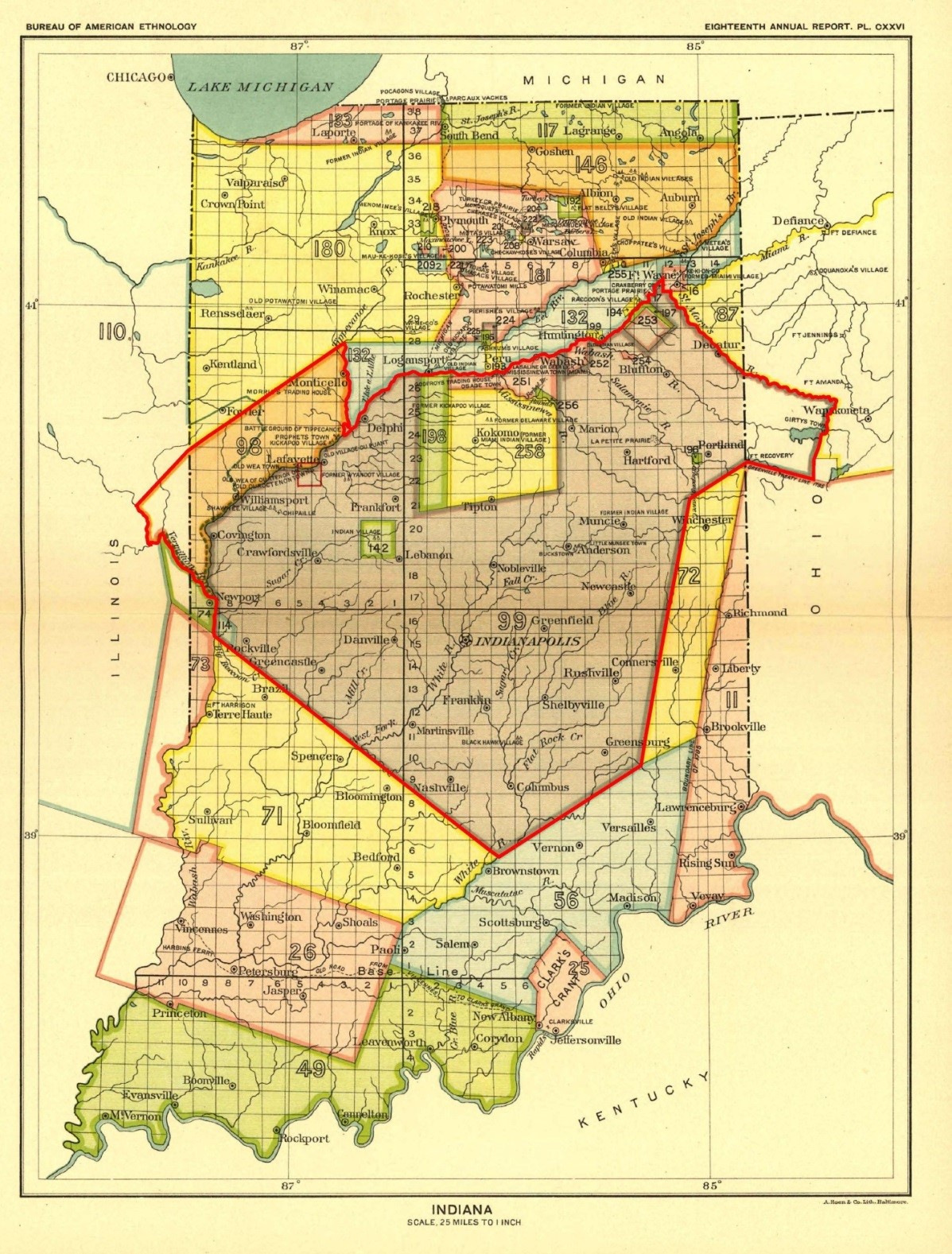

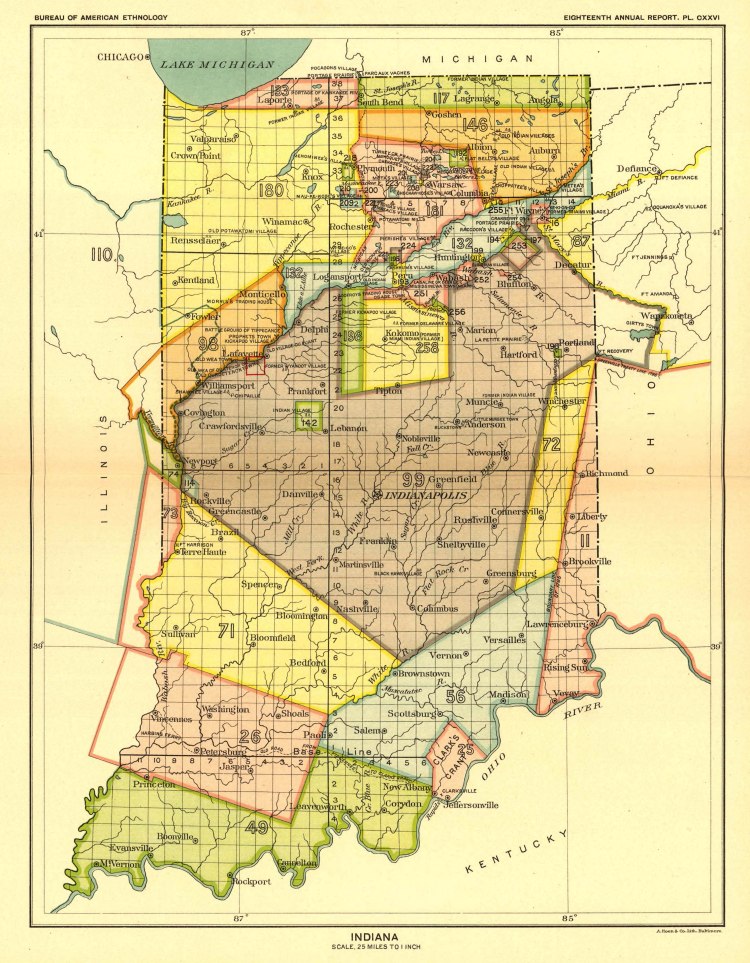

Surveyors working in Indiana will recognize this as a map of the Public Land Survey System in Indiana. The 2nd principal Meridian is there along with the baseline, the correction lines and the six mile townships. The determined, purposeful grid within which we work. But the feature of the map which jumps out, color coded with big thick borders, are the treaty parcels. The defined parcels of land to which the U.S. government gained title from the native inhabitants prior to surveying. These parcels represent the basic, underlying framework of the PLSS and should command the attention of any surveyor working near their boundaries. Although the federal government made every effort to blend the parcel boundaries seamlessly into the township and section grid, they are actually hard, fundamental boundaries which may, or may not, introduce an angle point into a section line. The unsuspecting surveyor, if not aware of the presence of the nearby treaty boundary, may never guess this angle point exists.

The basic information presented on this map is also shown on other maps and the true record of the location of the treaty boundaries is contained on the original township plats, with assistance from the original field notes. So why am I fascinated by this particular map? Honestly, it might be the colors. I confess that I find the pretty shaded parcels to be much more engaging and easier to process visually than a jumble of black and white lines. I’m not afraid to admit it, I think this map is pretty. Or it could be the fact that the treaty parcel commonly known as the Thorntown Reserve, located mostly in Boone County and shown here as a green square northwest of Lebanon, jumps right off the map. I work for the Boone County Surveyor. I am currently in the process of determining the exact boundaries of the Thorntown Reserve, a most interesting survey puzzle if ever I met one. Hence, I genuinely appreciate that this map makes the Thorntown Reserve so much more prominent than any other similar map I have seen.

But I am really drawn to this map for another reason. It is the numbers. Every parcel is denoted by a two or three digit number, such as the “99” prominently displayed above the word “Indianapolis.” If one is interested in the history of Indiana, those numbers make this map a gold mine. They are the key to the actual treaties by which the U.S. Government gained title to the land from the native inhabitants. Better yet, those numbers provide a rich resource for the study of U.S. history in general, as this map is one of a series of 67 similar maps which show the treaty parcels across the U.S.A.

So who made this remarkable map and its 66 companion maps and how do they work? They are all the product of research by Charles C. Royce and are included in the Eighteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1896-1897, contained within U.S. Serial Set Number 4015, 56th U.S. Congress. They are federal publications commissioned by Congress. Each number, such as that “99” by Indianapolis, correlates to a chronological record in tabular data format, also included in U.S. Serial Set 4015, summarizing critical information about the relevant treaty. State, date, tribe, general land description, reserves and historical narrative are all contained in the table. If you are interested, please go to your favorite search engine and type “royce land cession maps.” All will be revealed. But it gets better. Once you’ve found the summary, you can use the information about tribe and date to access the actual text of the treaties in a digital repository hosted by Oklahoma State University. The treaties can be interesting reading with their variously detailed land descriptions and promises of compensation, future rights and other matters which were all very important at the time.

Meanwhile, back to the map. What is it about the treaty parcels that are so interesting? There is, of course, the issue of the fact that they are true, although often subtle, boundaries within the PLSS. That should make them less than a mere curiosity to any surveyor. But there is more. There is the story they tell. The oddly shaped, generally non-cardinal orientation of the parcels speaks of the U.S. Government’s determination to get title to whatever piece of land it could, whenever and however it could be arranged. And there is the story of the native tribes and their concept of land ownership. The story of where the different tribes were and when. The story of with whom the U.S. government negotiated, why a specific tribe was included in the negotiations and how they interacted with the other tribes. When reading that story, the state of Indiana is perhaps the most interesting state in the whole country. My research indicates that by the time William Henry Harrison was governor of this territory, charged with securing treaties to the land, the Indiana Territory had become a busy place. Numerous tribes were bunched up here, having already been displaced from elsewhere. Why were the Delaware hunting along the White River in east central Indiana when they were really the Lenape from New Jersey? Why do we hear so much about Chief Tecumseh and his brother the Prophet making such an impact in Indiana when they were Shawnee, originally from Ohio? This was traditionally the country of the Miami and their associated tribes. They were sharing their land with other tribes.

Ultimately, though, it is the Miami who most influence the map of Indiana. In part, perhaps, because they were the primary native inhabitants of the land, but more so because they were savvy negotiators. By the time the young state of Indiana had come into existence, the Miami had intermarried substantially with French fur traders. Rights in land? Sale of land to the U.S. government? The old story is that the native inhabitants had a different concept of land ownership than the European descendants and that they did not fare well in negotiations. That story is partially accurate but it does not take into account the influence of the French fur traders on the Miami. Led by their French descendant chiefs, the Miami were excellent negotiators who fully comprehended the value of the land they inhabited. That comprehension and the resulting negotiations significantly influence how this map turned out and in turn influence the history of Indiana. The Thorntown Reserve? That was the Eel River tribe of the Miami. Parcels 198 and 258, the Great Miami Reserve? Yep. In negotiating the New Purchase (number 99), the U.S. government wanted all of the land south and east of the Wabash River. The huge piece of land around Kokomo represents some tough negotiations on the part of the Miami Chiefs. It also radically influenced the direction of U.S. Highway 421, Michigan Road, as it leaves Indianapolis, but that is another story. And just look at the land in the northeastern part of the state. Talk about negotiations and treaty boundaries. Wow! Still, I think the nice square Thorntown Reserve is interesting.